The visionary

Cassandra Baldini

- Career & Business

A note to Aboriginal and Torres Strait readers: This story contains the image and name of a person who has died; discretion is advised.

In 1981, after years of campaigning for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander land rights in Australia, Eddie Koiki Mabo stood up and addressed the Land Rights Conference at James Cook University in Townsville.

Mabo explained the traditional land ownership system upheld in the Torres Strait and specifically the practices of the people who had owned and occupied Mer Island (Murray Island), his birthplace, for over 60,000 years.

In his speech, Mabo stated that he would not reference books written by academics; instead, he explained that his textbooks were his parents, his community and those who walked alongside him in culture.

Among the audience was junior lawyer Greg McIntyre, who listened intently as Mabo spoke about the historic land inheritance practices dismissed under the myth of ‘terra nullius’ during the invasion and subsequent annexation of the Torres Strait to Queensland in 1879.

McIntyre had also been invited to speak at the conference.

“I was asked to attend the conference because someone had heard about my research on Aboriginal land rights within common law,” McIntyre explained.

While conducting his research, McIntyre realised that First Nations land rights were not recognised in Australian common law. This information encouraged the young lawyer to develop a thesis, leveraging a global stage.

“My thesis was that in England, they recognised local legal rights, which are not the same as the broader common law rights. I thought, if that could be done in England in the 16th, 17th, and 18th centuries, why can’t they recognise local Indigenous rights in Australia?”

“At that time, I wasn’t calling it Native Title, I was calling it Land Rights Being Recognised in Australia. I presented my idea at a national conference in Canberra in the late 1980s at the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies.”

Word of McIntyre’s work started to spread.

“Someone heard about my work and I was invited to present a session called ‘A High Court Test Case?’ at the Land Rights Conference in ’81,” he said.

“What I didn’t know at the time was that the event was co-managed by the James Cook University Student Union and the Treaty Committee of Townsville, of which Eddie was a co-chair and also a presenter on the day.”

Following the closure of the speeches, groups broke off to discuss the findings and determine if action should be taken.

“I wasn’t in that meeting, but the group dealing with Torres Strait land rights was adamant that they should pursue the concept behind the land rights thesis as a test case,” he explained.

“It was asked, ‘Who are we going to have as a solicitor?’ The response was, ‘Well, young Greg McIntyre will probably be able to do the job.’”

Meeting the visionary

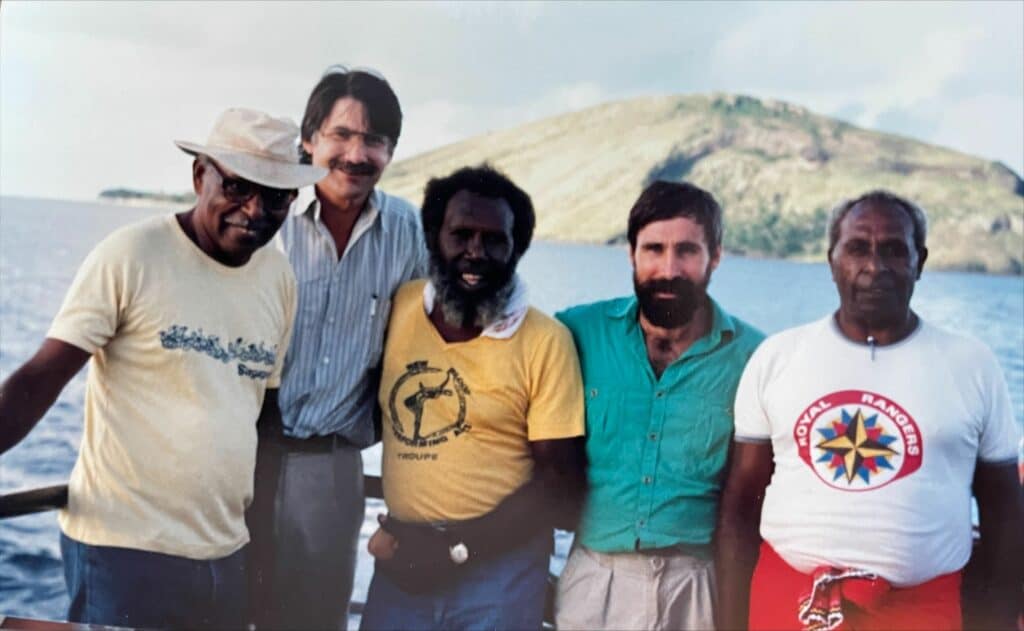

It was then that McIntyre first met Eddie Mabo.

“Eddie was a person with vision,” McIntyre said with unwavering certainty.

“Eddie was always very enthusiastic. He was an activist by nature. He had set up the Black Community School in Townsville and was instrumental in that, serving on the board and, I believe, teaching there as well. At that time, he was also the chair of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Legal Service, Townsville Committee.”

At that moment, it was decided that Eddie Mabo, with the help of McIntyre, Barbara Hocking, Ron Castan QC and Bryan Keon-Cohen, would pursue a claim to obtain land ownership recognition for territories located on Mer Island.

Mabo, along with his co-plaintiffs David Passi, Sam Passi, Celuia Mapo Salee, and James Rice, commenced court proceedings. However, no one could have anticipated the immense self-determination required to see the case through to the end.

McIntyre reflected that it was a challenge for all involved.

“It was very difficult for Eddie, but he was a stayer,” he said.

McIntyre, who was responsible for securing funding to see the case through, recalls that particular challenge.

“I managed to secure most of the funding for the case, but when it came to covering Eddie’s travel expenses from Townsville to Canberra, the Attorney General’s department refused, stating his presence wasn’t necessary. Eddie, determined to be there, paid his own way,” McIntyre laughed.

Funding was a constant struggle. Initially, McIntyre received a $50,000 grant from the Minister for Aboriginal Affairs, who was annoyed that he had applied after starting the proceedings. Later, he obtained another $3,000 grant, thinking it would suffice, but the case dragged on.

“I turned to the Attorney General’s department for additional funding, but their payments were slow, forcing me to find interim funds. I used airline credit accounts to bring witnesses from the Torres Strait to Brisbane, but eventually, I couldn’t cover the costs and lost my credit cards,” he said.

In an attempt to cut costs, McIntyre and Mabo would share hotel rooms while travelling.

“We shared a hotel room in Brisbane because money was running out. Eddie gave evidence for most of that time in the witness box, then we’d come back to our hotel and he’d do a drawing of the blocks of land that he was going to talk about the next day,” McIntyre reflected.

McIntyre recalled Eddie fishing in the canals of Queensland while staying on the Gold Coast during some time off between hearings.

“Rather unsuccessfully,” he laughed.

At the time, the Queensland Government challenged Mabo’s land claims, arguing he didn’t own the land he claimed because he had been adopted into the Mabo family by his uncle after his mother’s death.

The team faced further setbacks in the initial phase of the case, as they had to defend against Queensland Parliament’s strikeout application, which argued that the concept of land ownership being pursued did not exist.

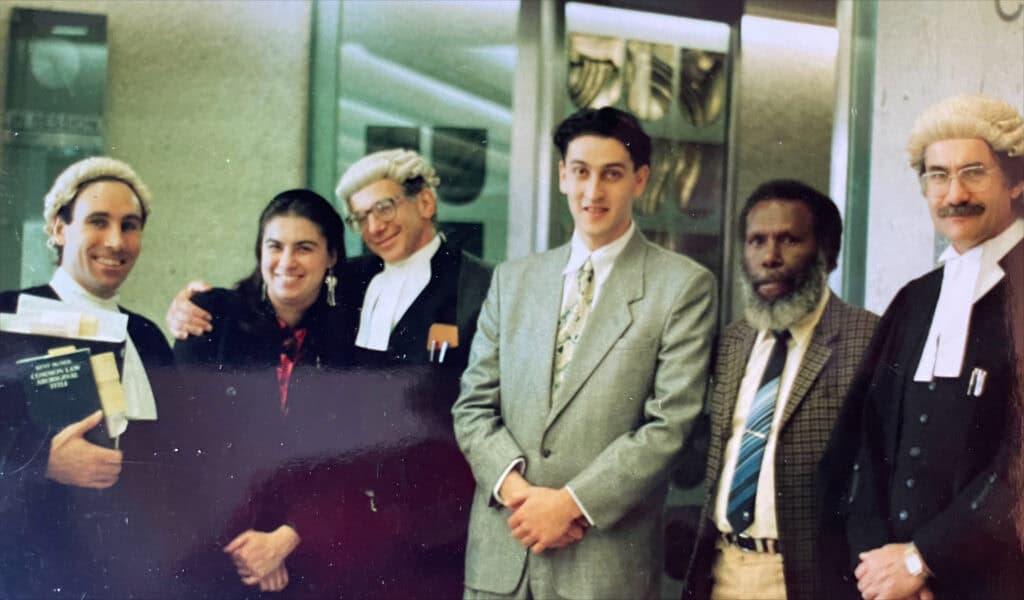

To the High Court

As the months rolled on, it was mutually agreed by both parties that they would present their own agreed facts in a meeting before appearing in front of the High Court.

McIntyre and the legal team managed to find significant evidence, including historical records that dated back to the late 19th century, supporting customary land rights.

“We spent several months, close to a year accumulating that material and gave it to the Queensland Government. And they said, ‘Oh, we can’t agree on all those facts.’ So, the idea that we were going to agree on a set of facts went out the window,” he explained.

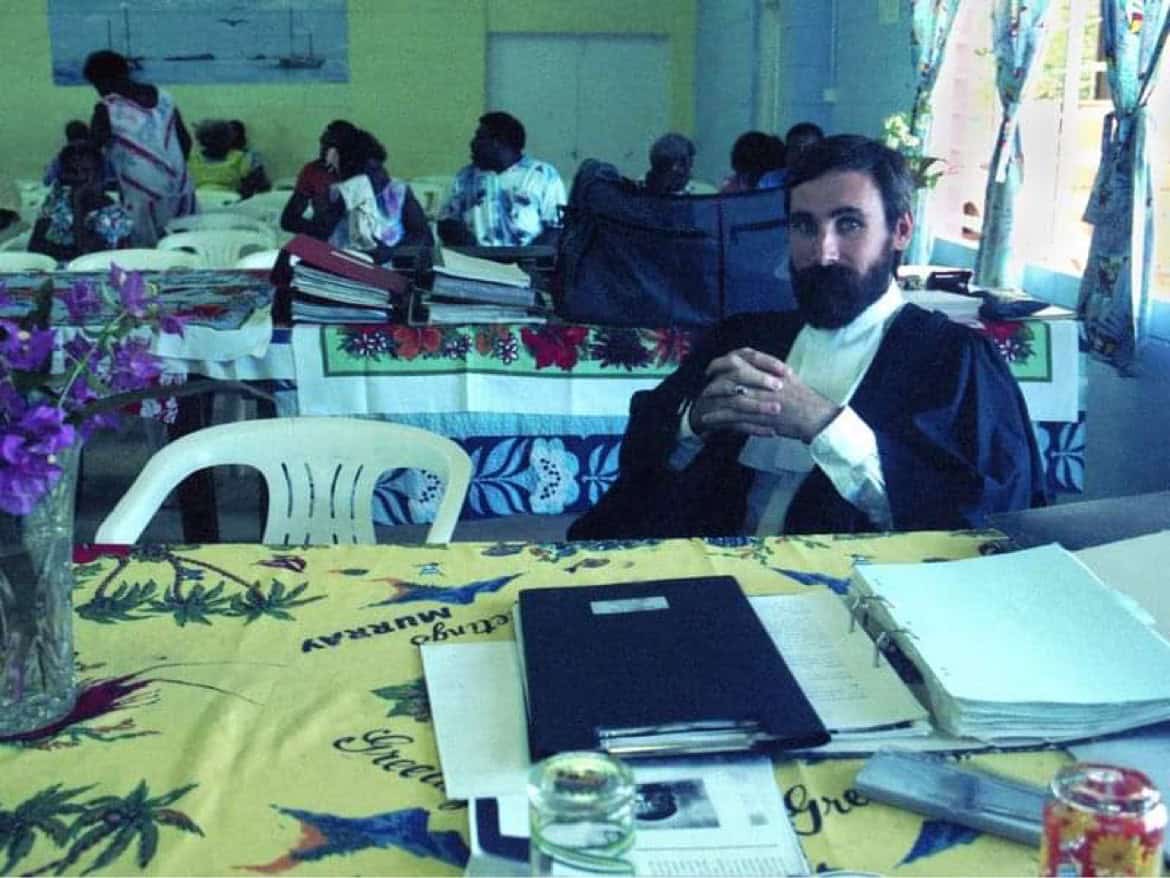

The case was then sent to the Supreme Court of Queensland, where it faced more than 300 objections from the Queensland Government on the ground of hearsay.

“We were worried the judge was going to say none of our evidence was admissible based on their scepticism around our evidence being hearsay,” said McIntyre.

“We sought a ruling from the High Court on the admissibility of traditional evidence, but the High Court instructed us to argue our case before the trial judge, who would decide on the evidence.

“In that moment, we thought, it was time to buy a computer.”

It was 1983, and little did McIntyre, Mabo, the plaintiffs, and the rest of the team know how much time lay ahead.

“But a lucky thing happened,” said McIntyre.

“The Queensland Government said, ‘We will stop jumping up and objecting to your claim. You know we object but why don’t you lead the evidence, and we will deal with it all at the end, as opposed to piece by piece.”

This allowed McIntyre and the team to get everything on record for potential High Court review.

But as months rolled into years and in 1985 the Queensland Coast Islands Declaratory Act was passed, declaring any title not given by the Crown, invalid.

“We delayed challenging this Act because High Court Justice Lionel Murphy was being prosecuted, leaving only six judges who might split their decision, with Chief Justice Harry Gibbs potentially casting the deciding vote against us,” said McIntyre.

“After Lionel Murphy was acquitted and returned, we challenged the Act in what became Mabo No. 1. We presented 13 arguments, succeeding on one under the Racial Discrimination Act, winning by a slim majority with Justice Stephen as the deciding vote.”

The historic tale of Mabo and his pursuit to reclaim land rights for the Meriam played out in court for a decade. Tragically, as a decision was on the horizon, Mabo became unwell.

“I rang up the registrar for the High Court, about six months after we’d argued the case, to say, ‘Look, Mr Mabo is really unwell. How do you think the judges are going?’”

Eddie Koiki Mabo passed away on the 21st of January 1992, five months before the Australian High Court would make its decision.

“The court did a lot of its own research, which is very unusual,” McIntyre explained.

“As it turns out, the court went away after we put our arguments in and looked at the whole colonisation of Australia in broad terms. They came to the view that the colonisation did not take away First Nations title and the common law had an obligation to recognise that title.”

‘Still a significant gap to be closed’

On the 3rd of June 1992, a historic moment unfolded. Fuelled by Mabo’s relentless pursuit, the Australian High Court recognised the traditional land rights of First Nations people, overthrowing the original claim of ‘terra nullius’ and introducing a legal doctrine of native title into Australian law.

To McIntyre’s surprise, the gravity of the decision spanned far beyond the Island of Mer and McIntyre notes that currently, 50% of the nation is the subject of favourable native title determination,

However, time has elapsed since the historic Mabo decision, and McIntyre agreed that Native Title isn’t a solution that fits modern-day needs.

“What we’re really now dealing with is the aftermath of that,” he said.

“What Native Title has done is lift the profile of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and provide them with a political position. But as we know, in terms of socio-economic outcomes, there’s still a significant gap to be closed, which requires something more. Recognition of our First Nations peoples is crucial, but we need to now move on to the next phase.”

McIntyre said he hopes to see the conversation move toward treaty and truth-telling more comprehensively.

“Native Title is more an underlay of political recognition, which now needs to be converted into what’s required in today’s world,” he concluded.

As an activist with a vision, staying committed to the legal pursuit of land rights was crucial to Eddie Koiki Mabo. Over ten years, the case faced numerous challenges, including a lack of funding, constant government push back and at a time potential lack of plaintiffs.

Nevertheless, Mabo’s self-determination, tenacity and relentless pursuit to stand up for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people prevailed. His story will remain engraved in history and the impact of the Mabo decision will always be felt across the nation.

Let us know if you liked this article

Let us know if you liked this article