Worimi Warrior

Cassandra Baldini

- Career & Business

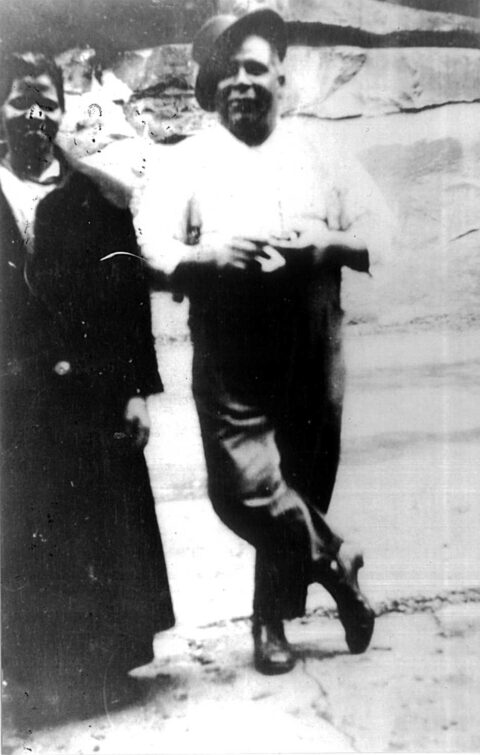

A note to Aboriginal and Torres Strait readers: This story contains the image and names people who have died; discretion is advised.

It’s been 100 years since Worimi man Fred Maynard and his fellow First Nations activists stood at the forefront of revolution, establishing the Australian Aboriginal Progressive Association (AAPA), the first Indigenous political organisation, in 1924. A century later, his grandson, Worimi man and Professor Emeritus John Maynard, explained how the creation of the AAPA laid the groundwork for the eventual establishment of NAIDOC.

Born in 1879 to Worimi woman Mary Maynard née Phillips, who was working as a domestic worker on a property near Hinton, Fred Maynard’s grandson John Maynard explained, that Fred had a harsh start to life.

“The stories go that before Fred was born, his mother fell pregnant to the old property owner, Mr Pierce,” Maynard explained.

“Amazingly, to cover up his misdemeanour, old Pierce paid a labourer on his property to marry my grandfather’s mother and he provided a residence for them.”

English-born labourer William Maynard and Mary Phillips went onto have six more children. Fred Maynard was one of those six. Tragically, his mother died in childbirth with twins in 1884.

“When that happened, William Maynard took off and left all the kids. The Pierce family kept the firstborn son, who was actually Pierce’s child and all the other kids were put off the property. My grandfather and his brother, Arthur, finished up with a Minister at Dungog,” Maynard said.

Stories passed down through the Maynard family explain life with the Protestant minister didn’t get easier for the brothers.

“The oral stories that were passed down to my father, my uncles and aunties, was that my grandfather said the minister was the cruellest man that ever walked the planet,” said Maynard.

At only five and six, Maynard explained that Fred and his brother Arthur were responsible for all menial tasks on the property which extended into a dairy farm. However, like all staunch activists, a light was about to flicker preparing Fred for what was ahead.

“The minister had a large library and he instructed both the boys to read and write. I don’t think he realised what he was arming my grandfather with at that particular point in time because by the age of nine to 10, it’s said that Fred was conversing with biology, philosophy and history,” Maynard explained.

Having had enough of the minister’s ill-treatment the boys took off at 13 and 14, travelling from Dungog to Sydney.

“How they got to Sydney is unanswered, but they made their way. One of their older sisters was working in a laundry so that’s where they headed, “Maynard explained.

The Maynard family recall Fred travelled widely as a prospector and a timber-getter before working on the docks in Sydney as a wharf labourer.

“That certainly moulded his political mindset as well,” said Maynard.

“I mean, certainly the trade union movement, but coming into contact with overseas black merchant sailors. He (Fred) gained black manifestos, black newspapers and black politically motivated books written overseas.

“‘It was also in conversations with these visiting merchant sailors that he (Fred) realised that the racism, prejudice and oppression that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people were facing in Australia wasn’t just local. This was a global thing and it needed to be recognised and fought in that way.”

A journey of self-determination

Initially, Fred was connected with an organisation that formed in Sydney, called the Coloured Progressive Association, which was largely made up of transient merchant sailors who were of African American, West Indian African, Islander and Māori descent.

Inspired by meeting heavyweight African American champion boxer Jack Johnson and joining activist Marcus Garvey’s global black nationalist movement, Fred began a journey of self-determination.

“Garvey-ism was all about social, economic and political reform. It was about self-determination. It was about black building, black pride in a sense of connection to country,” said Maynard.

“In the Garvey sense that was African Americans looking back to Africa. But for us, I mean, it really resonated that we were still connected to country. It was under our feet. So, the importance of country and the Garvey message really ran very strong.”

Marcus Garvey was imprisoned in the US In 1923 which led to the collapse of his movement. However, one year later the AAPA was formed with Fred at its helm.

“It’s amazing the things the AAPA put up as a political platform. They were a huge mobilisation of Aboriginal people and the catalysts for two main things; the revocation of independent Aboriginal farms and the acceleration from about 1910 which saw Aboriginal kids torn from their families,” explained Maynard.

Maynard noted that before the establishment of the NSW Aborigines Protection Board, Aboriginal people in New South Wales and occasionally in other states managed to regain land throughout the mid-19th century.

To reclaim land, Aboriginal people and their non-Indigenous supporters would submit petitions, prompting government representatives to inspect the land, often resulting in the granting of acres of traditional country.

“The archival records of these police reports sent back to state governments often said, ‘It’s heavily timbered worthless scrub; give it to them,” recounted Maynard.

“The police revisited the site repeatedly and the archival records show in 12 to 18 months the land had been cleared, cultivated with crops, homesteads built and livestock raised. It marked a prosperous period of 50 to 60 years for Aboriginal people.”

Maynard explained throughout this period Aboriginal people were winning blue ribbons in the agricultural shows, clearing hundreds of pounds.

“There’s even an account of an Aboriginal family buying their own piano, but it’s not at the loss of their culture,” he said.

“They were still speaking in their language, combining Western farming methods with Aboriginal subsistence and methods of food gathering. So, they had the best of both worlds. No one knew the seasons better than Aboriginal people.”

But by 1910, the Protection Boards were established. Maynard noted increasing pressure from white groups regarding Aboriginal land, which eventually led the Protection Board to start revoking independent farms.

“By then Aboriginal people had gained 27,000 acres. This was prime land in New South Wales, on the South Coast, the Mid-North Coast, the Far North Coast,” said Maynard.

“So Aboriginal people were thrown off the land, in many instances at gunpoint by the police. Nothing more to show for the four or five decades of labour other than the shirts on their backs. Told to get back into the bush. So, this was the main catalyst for the admission of Aboriginal political revolt, the loss of that land.”

Fighting for change

Within six months of its inception, the AAPA had over 600 members, 13 branches and four sub-branches in New South Wales. It held roughly three conferences, the first being at David’s church in Surry Hills. Maynard explained the organisation garnered front-page press coverage and demanded self-determination.

“That was the aim, ‘Aboriginals demand self-determination’, Maynard pointed out.”

“This was 50 years before the Whitlam Government was credited with putting up self-determination as an Aboriginal policy directive. So, it was Aboriginal people themselves that were pushing for that.”

In addition to demanding sufficient land for every Aboriginal family in the country and an end to the policy of removing Aboriginal children from their families, the AAPA also sought control over Aboriginal Affairs, advocated for the establishment of an all-Aboriginal board under the Commonwealth Government and called for the abolition of the Protection Boards.

“These points are groundbreaking Aboriginal political directives. These are articulate, eloquent, Aboriginal political spokesmen and women, and as I said, decades and decades, ahead of their time.”

The groundwork for NAIDOC

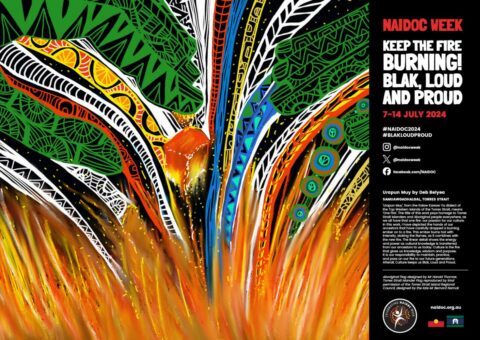

Fast forward 100 years, amidst the celebration of NAIDOC, Maynard explained that his grandfather and other staunch Aboriginal leaders have played a pivotal role in paving the way. Their efforts and activism laid the groundwork for significant advancements in Aboriginal rights and recognition.

“The AAPA is the leader to NAIDOC,” Maynard said.

“Of course, the push for the National Aboriginal and Islander Day Observance Committee came following 1938, the Day of Mourning,” said Maynard.

“You had people like William Cooper, Jack Patton, Bill Ferguson, Curly Gibbs, Doug Nichols, Bill Onus, who were all a part of that. One of the things that they discussed was organising a national, Aboriginal and Islander Day of observance.’’

NAIDOC, originally NADOC (National Aborigines Day Observance Committee), evolved into a week-long event in the 1970s.

“NAIDOC recognises and celebrates Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people and their unique culture, spanning 65,000 years of history,” said Maynard.

‘”My grandfather said we have overriding rights above all others to our land. And it (NAIDOC) gives pride and inspiration to Aboriginal people.”

Between 1927 and 1929 the AAPA was forced to close its doors due to a lack of support and government pressure.

“In many instances, AAPA members were harassed and hounded out of existence by the police acting for the Protection Board. You’ve got to look back and note that the chair of the Protection Board was actually the New South Wales Police Commissioner. So, there was a lot of police harassment,” he explained.

“But the platform that they put up, in reality, is a lot of the things that we’re still fighting for, land rights, self-determination, protecting our family and kids, defending a distinct Aboriginal culture identity and that Aboriginal people be placed in charge of Aboriginal Affairs. So, it was a groundbreaking movement and that legacy still continues through to today.”

Despite a journey marked by struggle, Aboriginal activists in the early 20th century remained resilient and demanded recognition as the original owners of the land, asserting their inherent rights.

This recognition brings pride and inspiration to Aboriginal communities, who have historically been misrepresented or omitted from mainstream narratives.

Preserving, acknowledging and learning about Aboriginal history, culture and traditions is crucial not just for Aboriginal communities but the nation’s population. It highlights that our greatest asset lies in the rich cultural heritage and deep-rooted connection to the land held by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

Looking at how his own story is intertwined with that of his grandfather’s Maynard said after leaving school at 15 in 1969 he had not even considered academia or going to university. Instead, he spent 25 years in various jobs. It wasn’t until the age of 40 that education found him.

“My father, to give me a kick up the bum, wanted me to write up my grandfather’s story. We carried stories, letters, some photographs and that sort of stuff. It was just going to be putting it up into a nice exercise book,” he said.

“I was to go out and search for more information and also interview people—family members, extended family members and those who knew my grandfather.”

In search of answers about Fred and the AAPA Maynard went to the Wollotuka Education Centre at the University of Newcastle.

“I thought just to ask them for other areas that I might explore in putting this together…and I was kidnapped into doing a diploma of course,” Maynard laughed.

”So, I did a two-year diploma, then I did a BA and then I did a PhD and following that I was made a professor.”

Fifteen books later, one of Maynard’s PhDs focused on his grandfather and the history of the AAPA. This research culminated in the book titled ‘Fight for Liberty and Freedom,’ originally published in 2007 was recently reissued this year to commemorate the centenary of the AAPA.

“I’ve got six folders full of material gathered that tells the story of that fight over the 1920s, which is truly amazing,” he said.

“But that’s the important message to our Mob: get out there and do your histories and put this stuff together. Aboriginal history in this country is like a giant jigsaw puzzle with most of the pieces missing. We’ve all got a part to play in putting pieces back onto the board and filling those missing pieces. This is just one example of such an important area of history.”

Looking ahead, Maynard acknowledges the fight for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander rights continues, yet he affirms that the spirit of self-determination within communities remains resilient.

“We’ve made significant progress since my grandfather’s time. Today, we have Aboriginal lawyers, doctors, and even pilots. These advancements highlight the progress driven by Aboriginal people, underscoring the importance of pursuing and sharing our history and achievements,” he concluded.

Let us know if you liked this article

Let us know if you liked this article